SPRING, 1967. I was twenty, a sophomore at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. I had just spent my first extended time out of the country on a semester abroad in Franco’s Spain. The Vietnam War was raging, and there was upheaval on campus.

SPRING, 1967. I was twenty, a sophomore at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. I had just spent my first extended time out of the country on a semester abroad in Franco’s Spain. The Vietnam War was raging, and there was upheaval on campus.

Freshman year I took a seminar, “Freedom and Liberation in Ancient China and India,” that stirred an interest in Taoism and Buddhism. At the same time, I started smoking pot and experimenting with mescaline, DMT, and LSD. The visual and lyrical effects of psychedelics stimulated my artistic, philosophic, and poetic intuitions and expanded my inner and outer horizons. They didn’t improve my academic standing.

That spring a flyer appeared for a guest lecture by Richard Alpert, Ph.D., formerly a psychology professor at Harvard, who had done some of his graduate work at Wesleyan. Two of his former students, Sara and David Winter, were teaching psychology at Wesleyan and had invited him to speak.

Alpert was vaguely notorious to me as an associate of Timothy Leary, a counterculture icon. They had both been fired from Harvard in connection with their psychedelic activities. Alpert had the distinction of being the only tenured professor ever publicly exorcised from Harvard’s Ivy League faculty. They didn’t go quietly. Dr. Leary’s infamous 1960s commandment “Tune in, turn on, and drop out” had become a media mantra and a cultural strategy. Pot and acid made rapid inroads, displacing alcohol as drugs of choice. The Beatles and the Stones tripped out, and there was an atmosphere of intrepid inner exploration and raucous fun mixed with political outrage. Some of it was hedonism, some was dumb, and some of it became the bones of a generation.

Dr. Alpert’s talk began at 7:30 P.M. in one of the student lounges. I expected a pep talk on “better

living through modern chemistry” (then an ad slogan for DuPont Chemical). About fifty people attended, mostly students, spread out on couches, chairs, and the carpet. Instead of a tweedy Harvard psychedelic psychologist, the speaker entered wearing a scraggly beard, sandals, and a kind of white robe or dress. Dr. Alpert had just returned from India, where his name had been changed to Ram Dass. He said it meant “servant of God.” He looked like a soapbox prophet in Hyde Park, which I’d just seen in London.

Instead of an opening paean to psychedelics, he began to relate his experience of living for six months in an ashram in the foothills of the Himalayas. He described meeting a guru who had a cataclysmic effect on his consciousness, so much so that he sequestered himself for six months in the guru’s ashram to learn yoga and meditation. This was too weird for a portion of even this avid audience, and before long some departed. After a while, someone turned out the lights, and Ram Dass continued to talk in womblike darkness. In the dark, his disembodied voice fairly crackled with a kind of energy that permeated the room. He combined the excitement of a scientist with a new discovery and

an explorer in terra incognita. He continued describing his experiences and responding to questions until 3:30 A.M.

As Ram Dass spoke of the interior transformation he had undergone, I began to experience one too. Subjectively it was like a figure-ground flip when, in one of those high-contrast images, you suddenly see the space instead of the shape. In my case I went from being the center of my universe to seeing myself as just one spark of awareness among billions. I understood in that moment that we are all on an evolutionary journey toward realization through infinite time and space.

It was more than a conceptual understanding. There was a feeling of meeting together in a deep space of love, and compassion for what Ram Dass called “our predicament.” Two and a half years later, when I traveled to see the guru in India, I experienced precisely this feeling again, like déjà vu. However it happened, an old man in a blanket, whom I also came to call Maharaj-ji, came through Ram Dass that evening. The abode of love, compassion, and oneness in which the guru lived had moved temporarily to Connecticut.

To a twenty-year-old on an intensely personal quest for identity, this was revelatory. The idea that there were other beings who had actually made and completed this journey of inner exploration that I had only imagined was astounding. Maybe the journey wasn’t quite so personal after all.

The next day I sought out Ram Dass and visited with him at the Winters’ home. Something had clicked that needed further exploration. Whatever I had experienced, I wanted more of it. I have almost no recollection of what was said between us in that exchange. I know I felt awe and gratitude, though as we talked I realized Ram Dass was very much on his journey, as I was on mine. Later I came to realize he sometimes had a difficult time when people associated him with the transmission of that state. What could he say? “Sorry, that wasn’t me talking”? I think it drove him to work harder on his own “stuff.”

He was always completely, refreshingly out front about his own desire system and need for approval, and he used his neuroses as “grist for the mill.” Rather than sweep things under the rug, he used the meanderings of his psyche as humorous fodder for

his talks. There was no “holier than thou.” It was more wholly than holy, more practical than pious. I think other people, too, appreciated how Ram Dass used himself as a case study for his inner research. The confluence of his psychological training, his openness from psychedelics, and his synthesis of Eastern religion made him a perfect resource for consciousness evolving during the upheaval of the 1960s. He managed to bring it together in understandable language. And it didn’t hurt that he told a good story.

Over the next two years I drove up periodically from Wesleyan to visit Ram Dass, following I-91 from Connecticut through Massachusetts to where he was staying at his family’s summer place, a farm on a lake near Franklin, New Hampshire. In warm weather he stayed in a tiny guest cottage without water or plumbing that he made into a cozy retreat, or kuti, where he meditated, practiced yoga, and cooked a daily pot of khichri, rice and lentils mixed together. In the winter he moved into the servants’ quarters of the main house in the attic over the kitchen.

Ram Dass taught me the basics of yoga and meditation and recommended some of the writings

of the saints and yogis he had come to know of in India. Pranayama (breath energy practices) and saying mantras (sacred syllables) became part of my routine. I learned to cook khichri and make chapatis, Indian flatbread.

Ram Dass’s father, George Alpert, was a lawyer who had been president of the New York, New Haven, and Hartford Railroad. He and his fiancée, Phyllis, were often at the house when I came up to visit Ram Dass in Franklin. They were extraordinarily hospitable, and I felt like extended family. Clearly Ram Dass’s new manifestation had left them at a loss after his career at Harvard, but they loved who he had become, and they didn’t really care why. George continued to call him Richard and seemed bemused by the assortment of mostly young people who kept turning up. It was all a bit of a mystery, but the love had infected them too.

Although he was mostly a hermit that year, in 1967 Ram Dass also gave a talk at the Bucks County Seminar House in Pennsylvania. In Franklin, along with his daily sadhana, or spiritual practice, he worked on a manuscript about his experience in India. In the winter of 1967–68 he gave an extended

series of talks at a sculpture studio on the East Side of Manhattan. The same people showed up night after night, often with friends. Others were beginning to be affected by the extraordinary energy and presence that accompanied his talks.

Ram Dass spoke with self-deprecating humor, using his own missteps as counterpoint to the intensely serious journey he was illuminating. His self-revealing honesty in facing his personal demons and his delight in the absurdity of a Harvard psychologist encountering Eastern mysticism became hallmarks of his presentations. He linked his psychedelic drug experiences, which many of us had experienced by then, to the dissolution of the ego in Eastern philosophy. And he used his encounter with the guru as a model for attaining the higher consciousness he now saw as the goal, enlightenment.

Soon after graduation from college in 1969 I was drafted and called in for a physical. Bearded and hirsute, I stood in my underwear with a string of prayer beads repeating a Hindu mantra during the entire day of prodding and poking. The psychologist was the last station along the line, and by the time I

arrived at his station I had been praying with such intensity I could hardly see. The psychologist, who looked as though he was unhappily doing his alternative service himself, disqualified me. I was put in a 1-Y and later a 4-F classification, which meant unfit for service. That left me free to join the young people, students, hippies, flower children, and others who had heard Ram Dass in person or by word of mouth and were arriving at the driveway in Franklin. My younger brother and sister went to the rock festival at Woodstock while I meditated at yogi camp with Ram Dass.

Outdoor weekend darshans, spiritual gatherings with Ram Dass, evolved under a tree in the yard, with George’s gracious permission, into summer camp. We were a ragtag group of twenty to thirty on an “Inward Bound” adventure. Tent platforms and a darshan house went up in the woods above the farm, and Sufi dances and yoga classes were held on George’s beloved three-hole golf course. Group meditations and yoga were part of the daily schedule, as Ram Dass sought to transfer his experience in India to this motley cadre of would-be

yogis. We made up with enthusiasm and love for what we lacked in disciplined renunciation. By summer’s end the weekend crowd under the trees numbered in the hundreds. Some of the campers were like ships passing in the night, some have perished, and others are still in touch, now grandparents.

Ram Dass’s painstakingly written manuscript about his India trip found no takers in the publishing world. He continued giving public talks, and that fall he drove cross-country to California to teach at a nascent center for psychological and spiritual growth in Big Sur called Esalen. Esalen assigned him housing with a writer and his wife, John and Catty Bleibtreu. John noticed the transcripts from Ram Dass’s talks at the New York sculpture studio as he pulled the suitcase out of his car. He asked if he could take a look. He thought there were some good stories, and he checked off the ones he liked.

From Esalen, Ram Dass drove to the Lama Foundation near Taos, New Mexico, a back-to-the- land commune of artists and hippies that he had helped found before his trip to India. Steve Durkee, a visionary artist who had spearheaded an art group

called USCO in New York, was a friend and the main man at Lama. He also noticed the transcript and asked what it was. Over dinner with five or six of the resident artists at Lama, they brainstormed ways that the passages John Bleibtreu had checked could be illustrated.

During the fall and winter of 1969–70, Ram Dass, Steve, and the Lama commune went to work on making Ram Dass’s words into text art. At his talks Ram Dass gave out postcards that people could send in to Lama to get a copy of whatever emerged. I even did my part and copied some of the photos of saints Ram Dass had brought back from India.

In early 1970 the Bountiful Lord’s Delivery Service at Lama mailed out several thousand copies of a twelve-by-twelve-inch corrugated box, the contents and printing of which were financed from the proceeds of Ram Dass’s lectures. It was distributed at no charge. In the box was a core book from the transcripts called From Bindu to Ojas (Sanskrit for “From Material to Spiritual Energy”). It was printed on brown paper and hand bound with twine. Included were a booklet about Ram Dass’s journey to the guru titled HisStory, a section of spiritual practices

called the Spiritual Cookbook, holy pictures to put up on your refrigerator or altar (some of which are reproduced in this volume), a book list called Painted Cakes, and an LP record of chants and spirituals from the contemporary scene. It was a true do-it-yourself kit for a spiritual journey.

The summer of 1970 saw a brief revival of the yogi camp at Franklin. After Ram Dass had been on the road and lecturing for a year, the numbers began to be overwhelming for George’s farm. But from those evanescent groups came the genesis of a Western satsang, a community of seekers.

Ram Dass continued to lecture and travel, but was mindful that Maharaj-ji had told him he could return to India in two years. (Maharaj-ji is a common honorific in India that literally means “great king.” In this book Maharaj-ji usually refers to Ram Dass’s guru, Neem Karoli Baba, because most of the time that’s how he was addressed.) Finding himself beginning to burn out after all the public exposure, Ram Dass was thinking about going back to continue his work on himself. Demand for the Bindu to Ojas box quickly exceeded the supply from the original printing. Steve Durkee was working on turning it into a book with

distribution by Crown Publishers, with an editor named Bruce Harris. It was titled Be Here Now.

Ram Dass’s guru, whom he had referred to only as Maharaj-ji in his talks and the box, had told him not to tell people about him. However, Ram Dass gave permission for three of us “students” to write to a devotee in India to see if Maharaj-ji would allow us to come see him. Jeff Kagel (later Krishna Das), Danny Goleman (who later became the psychology editor at the NewYork Times and wrote a bestseller, Emotional Intelligence), and I wrote to K. K. (Krishna Kumar) Sah asking him to please request Maharaj-ji’s blessing on our journey to India to see him.

When K.K. was growing up, Maharaj-ji was a kind of foster parent to him, and he still considers himself something of a child in relation to Maharaj-ji. When Ram Dass first met Maharaj-ji, Maharaj-ji sent him to stay at K.K.’s home, so K.K. felt a special responsibility for Ram Dass. Years later K.K. related what happened when he took our letters to Maharaj- ji. He laid the letters on the bed where Maharaj-ji was sitting, and Maharaj-ji inquired what they were.

K.K. said they were from students of Ram Dass who wanted to come see him. Maharaj-ji said, “What do I have to do with these people? Tell them not to come!”

K.K. had been lovingly feeding Maharaj-ji slices of apple. Now he stopped. He put his head down and pouted. Maharaj-ji went on talking to other people and finally looked down at K.K.

“What’s the matter?”

“I can’t tell them that, Maharaj-ji. They are Ram Dass’s students.”

This went on for a while. Finally, Maharaj-ji said, “Tell them whatever you want.”

We got a letter back from K.K. in his exquisite hand. It said, “Maharaj-ji doesn’t invite anyone to come, but his doors are always open. If you should find yourself near Kainchi Ashram while in India ”

That nuanced response was enough to start us buying tickets and securing visas.

Instead of the expected culture shock on arriving in India, I felt completely natural. Everything was out on the street without pretense, nothing hidden. Even the beggars with deformities were part of some seamless, fragrantly decadent whole. We traveled

from Bombay (now Mumbai) to Delhi, and then from Delhi to Nainital, where we hoped to find K. K. Sah. The last leg of the trip was a twelve-hour ride up to the mountains on a gear-grinding, diesel-spewing

U.P. Roadways bus. Nainital is a “hill station” constructed around a scenic lake by the Brits to escape the summer heat of the plains. The atmosphere literally changes as the bus ascends miles of switchbacks from the dust and traffic below. From Nainital, coming down the last switchbacks from the hamlet of Bhowali into the valley of Kainchi, we caught glimpses of the orange spires of the ashram mandir (temple). I experienced a profound feeling of coming home, a little like the last miles to my grandparents’ place on Long Island, where we

would go for the summer after school let out.

As we arrived K.K. said, “Maharaj-ji, they are here now.”

Maharaj-ji said, “Feed them,” and sent a bunch of bananas.

It was a good sign. We were asked to take prasad, food. We sat down to piles of spicy potatoes and puris, deep-fried bread, on leaf plates. I ate three mounds of potatoes and seventeen puris.

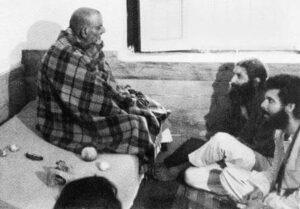

After eating, K.K. brought us to where Maharaj-ji was sitting on a wooden tukhat, or bed, in his “office.” There was no hesitation, no unfamiliarity.

Maharaj-ji told K.K., “They are good persons.”

K.K., who was glad the newcomers were being treated so well, replied without missing a beat, “I never bring bad people to you.”

Everyone laughed, and he proceeded to interpret for us. Maharaj-ji said we came from good families, and he played a bit with our clothing. Later we went back to Nainital to stay at a family hotel owned by K.K.’s cousins and were permitted to come back to the ashram every few days.

Meeting Maharaj-ji was a total flashback to that first night at Wesleyan. The feeling inside was the same, the same figure-ground reversal; I became a speck floating in the ocean of existence instead of the focal point of my own egocentric universe. Maharaj-ji’s overflowing love and affection made me feel completely safe. I was soaking it up like a sponge. Though I was meeting him for the first time, I felt as if I had known him and he had known me forever. I had come home, to a real home in the heart, to a family that transcended blood relationship.

Ram Dass eventually joined us in Nainital after accompanying Swami Muktananda on a world tour. By the time he arrived, it was nearly Thanksgiving, and Maharaj-ji had left the hills, which got very cold in winter, for the warmer plains. We didn’t know where he had gone, and we didn’t find him for more than a month. Actually he found us.

In 1972 after a year in India, Ram Dass stopped off in London and gave several lectures. Back in the United States, he found himself a spiritual celebrity because of the publication of Be Here Now, which

struck a cultural chord and had sold out several printings.

He traveled and lectured constantly. The year 1973 saw the publication of a six-record box, Love Serve Remember, which I and a number of those in the recent Indian cohort worked on. It was based on a series of talks with Paul Gorman on WBAI radio in New York and produced at a media commune called ZBS in upstate New York.

I delayed returning to India to complete the record project, and in September 1973 I had just arrived at Franklin for a visit with Ram Dass when a telegram arrived with news that Maharaj-ji had left his body— he had died. I went through a cascade of reactions one after another: grief, regret that I had not made it back, gratitude that I was among “family” when the

news came, and a realization that the bath of love was still there. Any of the Buddhist teachings on impermanence that had not taken hold were now being reinforced big time. It was all changing. Maharaj-ji’s new teaching was, “Sink or swim.”

Some of us made a brief pilgrimage back to India to visit the Indian family and view Maharaj-ji’s ashes. When we resumed our lives back in the States, there remained a strong presence of the guru, yet there was no form, and it was difficult to describe. Many in the satsang were inspired to service in some shape or form.

Ram Dass continued lecturing and teaching, published several more books, and worked to change models for social service, dying, and consciousness in the culture. He helped start a group called the Seva Foundation (seva means “service” in Sanskrit) meant to bring the values of karma yoga (the yoga of selfless service) to social action. I saw him periodically, though he was based on the West Coast and I was still living on Long Island.

Ram Dass had a murti (statue) of Hanuman, the monkey god of service and devotion, carved in

Jaipur, India, and shipped to the United States through the port of Los Angeles. While devotees searched for land for a Hanuman temple, this beautiful fifteen-hundred-pound white marble flying monkey took up temporary residence in Arroyo Hondo, New Mexico, on land belonging to one of our India crew.

There was disagreement among the devotees about how to consecrate the murti. Some wanted to do it with a Brahmin priest and full Hindu puja (worship rituals). Others were ready to open the box and just say hello. One of us, tripping on LSD, jumped into the crate with Hanuman and plowed through all the wood shavings, newspaper, and chips until finally he brought Hanuman into the light. Hanuman was then set up in a barn on the land. Later he moved with his host to a shed on the outskirts of Taos. Gatherings began to happen there to commemorate the annual anniversary of Maharaj- ji’s death (final merging or mahasamadhi). Eventually the land was purchased from the satsang member, and it became Maharaj-ji’s ashram in America.

In 1975 Hilda Charlton, a teacher in New York who

had introduced us to Swami Muktananda, met a housewife from Brooklyn who had experienced a transformation while learning yoga at a Jack LaLanne studio and was (supposedly) in communication with Maharaj-ji. Her name was Joyce; Hilda called her Joya. Hilda introduced Ram Dass to her by telling him Maharaj-ji was living in Joya’s basement in Brooklyn. Ram Dass was soon inducted into the inner circle and began receiving the accelerated esoteric course.

Joya was able to induce euphoric states in those around her, and she certainly seemed to enter into extraordinary out-of-body states herself too. Sometimes they were hard to distinguish from the constant melodrama that went on around her. The Joya saga continued for a couple years.

Ram Dass was spending time in New York. He and I began work on this book along with a photographer friend, Peter Simon. At the time it was envisioned as a photographic tour guide to spirituality in the West. Thirty-five years later it has become a deeper and more joyful reflection on the journey than either of us could have expected.

Ram Dass came to the belated conclusion that

Joya’s secret teachings were more hypocrisy than esoteric revelation, and he left. He gave a chagrined account of his experience in a front-page mea culpa i n New Age Journal titled “Egg on My Beard.” I stayed on longer in the Joya scene out of a misplaced sense of loyalty, and the manuscript sat on a shelf, forgotten for a couple decades. Joya caused many bridges to burn, and the one between Ram Dass and me took a while to rebuild. Gradually we resumed contact through the Seva Foundation, the ashram in Taos, satsang gatherings, events like the Home-Aid benefit in New York, and generally sharing Maharaj-ji’s love, which remains the constant glue in our lives.

Ram Dass was back on tour, speaking and leading retreats. When he wasn’t on the road, he lived in northern California with an artist he had formed a bond with, working on book and video projects, and a prototype for a radio call-in show.

In 1993 I met Kate. She attracted me, and our karmic stars were clearly and inevitably crossing. In November 1996, Ram Dass married us at her family’s summer place atop a hill on Martha’s

Vineyard. As my newly betrothed danced with Ram Dass at the reception, he seemed to pass out and collapsed on the dance floor. I was engaged with other guests and didn’t notice. He revived quickly and sat out the rest of the party. Kate said he was surprised at what had happened. The band played on, but later the incident seemed like foreshadowing. The next day he departed to lead a retreat in the Caribbean.

In February 1997 I had a call from Dr. Larry Brilliant, a satsang brother in California, who said Ram Dass had suffered a devastating hemorrhagic stroke, a bleed in his brain, and might not survive. It had probably happened during the night, and he had not been able to summon help until his manager, Jai Lakshman, called from New Mexico. Ram Dass managed to knock the phone off the hook. Jai, hearing no coherent response, said, “Are you in trouble? Tap once for yes, twice for no.” After a single tap he called Ram Dass’s secretary, Marlene, who lived nearby. She found him on the floor and called 911. Ram Dass’s survival and recovery were in doubt. People were praying for him on both sides of the world.

The next years were a Sisyphean struggle to adapt to disability and to regain first his speech and then as much body function as he could. His storytelling gift had disappeared into aphasia, and his right side was paralyzed. Fortunately, he is left- handed. His mind, his consciousness, remained completely intact, if not expanded. His heart, his sense of compassion, became a glowing jewel of pure presence.

Before the stroke Ram Dass had been working on a book about aging. Needless to say, his understanding and approach changed. Laboriously, and with assistance from another writer, Mark Matousek, Ram Dass completed Still Here, which was published in 2000. Few readers were aware of the magnitude of accomplishment required just to complete the manuscript. Mickey Lemle, a documentary filmmaker, made an amazing film about Ram Dass during this period called Fierce Grace. It chronicles Ram Dass’s passage to a deeper place in himself—an evolution that continues as he uses his own suffering as grist for the mill.

Ram Dass began traveling intermittently, lecturing and speaking at retreats, though on a much curtailed

schedule. The aphasia punctuated his talks in new ways, so they ran slower and deeper. His old friend Wavy Gravy, of the Hog Farm commune, said, “He used to be the master of the one-liner. Now he’s the master of the ocean liner.”

In October 2004 Ram Dass once more undertook a journey to India, to revisit the temple in the hills where he had first immersed himself in yoga and Hinduism and learned to search within without chemical enhancement. Kate and I and our by now two children, ages five and seven, made the journey independently, and we all met there for the harvest festival of the goddess, Durga Puja. It was an emotional and deeply moving pilgrimage for Ram Dass, one that he had thought he might never be able to make again. The simplicity, silence, and maternal affection of the surroundings were a source of great renewal and, even with the relatively inaccessible steps and doorways of the ashram and its bare-bones comforts, he thrived.

He stayed for about ten days, and our family remained for the rest of a three-month sojourn while he journeyed back to California via Singapore. It was a lengthy trip with stopovers, some thirty-six hours.

When he got back to California he was home for a day, then flew to Hawaii to conduct a long scheduled retreat on Maui. At the end of the retreat he developed a high fever and at the emergency room on Maui was diagnosed with an acute urinary infection that had migrated to his kidneys and into his bloodstream. Pope John had died from a similar infection.

We corresponded by worried e-mails from Rishikesh in India with Ram Dass’s caregivers. He was in the hospital for nearly a month. Once again he almost bought the farm. The bug he had was resistant to most antibiotics and made urinating exquisitely painful. By the time he got out of the hospital, he was weak and further travel was out of the question. Sridhar Silberfein, an old friend who had organized the Maui retreat, found him a house and helped set up a household so he could recover. It was slow going. Since then, with the exception of one trip to the mainland to visit the Hanuman temple in Taos, Ram Dass has stayed on Maui. The tranquil atmosphere and tropical climate are conducive to health and profound healing, as is a supportive

community.

When he wound up in Maui in November 2004, his finances, long dependent on lecturing and touring, were depleted. Maharaj-ji had told him not to accept his inheritance from his father, and Ram Dass had always raised funds for others’ causes. Friends, students, and supporters, notably author and teacher Wayne Dyer, a fellow Maui resident, rallied to raise money so Ram Dass could live there without traveling.

Having returned to New York, I went to visit Ram Dass in Maui in early spring of 2005. He was slowly regaining strength, eating better and working with an acupuncturist and Chinese herbal doctor, who thirty years before had been a student when Ram Dass taught the first summer at Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado. He was doing serious physical therapy again for the first time since he’d stopped a year after the stroke. Annual retreats began to be held in Hawaii. Another of Ram Dass’s first students, Krishna Das, now the chant master of the yoga circuit, joined him leading retreats that brought students from the mainland. A new website was set up at www.ramdass.org.

When we met again the following fall, we recalled the long dormant manuscript sitting in my basement. We decided it was time to bring it to light and see what was there. As we tried to make sense of what we said in the 1970s, reworked it, and brought it into the present moment, a kind of joy suffused the process. The 1960s and 1970s are long gone, yet the sense of unconditional love that was awakened then—the ocean tide of the guru’s compassion, the journey set in motion within us—is still the beacon of our shared universe.

Over the years something has crystallized in Ram Dass. Elements from the rainbow of his experiences in academia, psychology, psychedelics, India, and the stroke have coalesced into a clear white light of wisdom. Working with him, I have new appreciation for the nuance of his perceptions about the layers of consciousness. When I wax pedantic, he brings it back to the heart. When I am mired in ego, he subtly changes the point of view to the soul.

Our karmic calamities, the grace notes of circumstance, the twists and turns of this path, are an unfathomable mystery. Exploring its dimensions with Ram Dass, chuckling over the illusions, missteps,

and potholes along the way, is a delight. Change is the only constant; the more things change, the more they stay the same.

It’s only love. There is nothing more. May we all be loved, and be love, now.

Be Love Now Ram Dass